Business

9 April 2025

Life on the ice

Researching the changes in Antarctica.

Antarctic Ambassador

Daniel Price

Life on the ice researching how changes in Antarctica will affect New Zealand and the entire planet.

Visiting Antarctica for the first time must have been quite an experience?

Everyone remembers their first time vividly. It's as close as you can get to go to another planet, without leaving Earth. I was 23 and it was incredible. The first time I saw Antarctica I was up in the cockpit of a US Air Force C-17 with the pilots, and the mountains came into view on the horizon. That was a special moment.

Landing there is something else. The doors open and you are immediately hit with the crispest, cleanest air in the world. It’s a kind of sensation you haven’t had before. Then you step off onto the airfield, and if you're lucky enough to have nice weather you've got Erebus in the distance – this beautiful, ice-covered volcano glistening in the sun and smoking away. An incredible sight.

What's the main focus of your work on Antarctica?

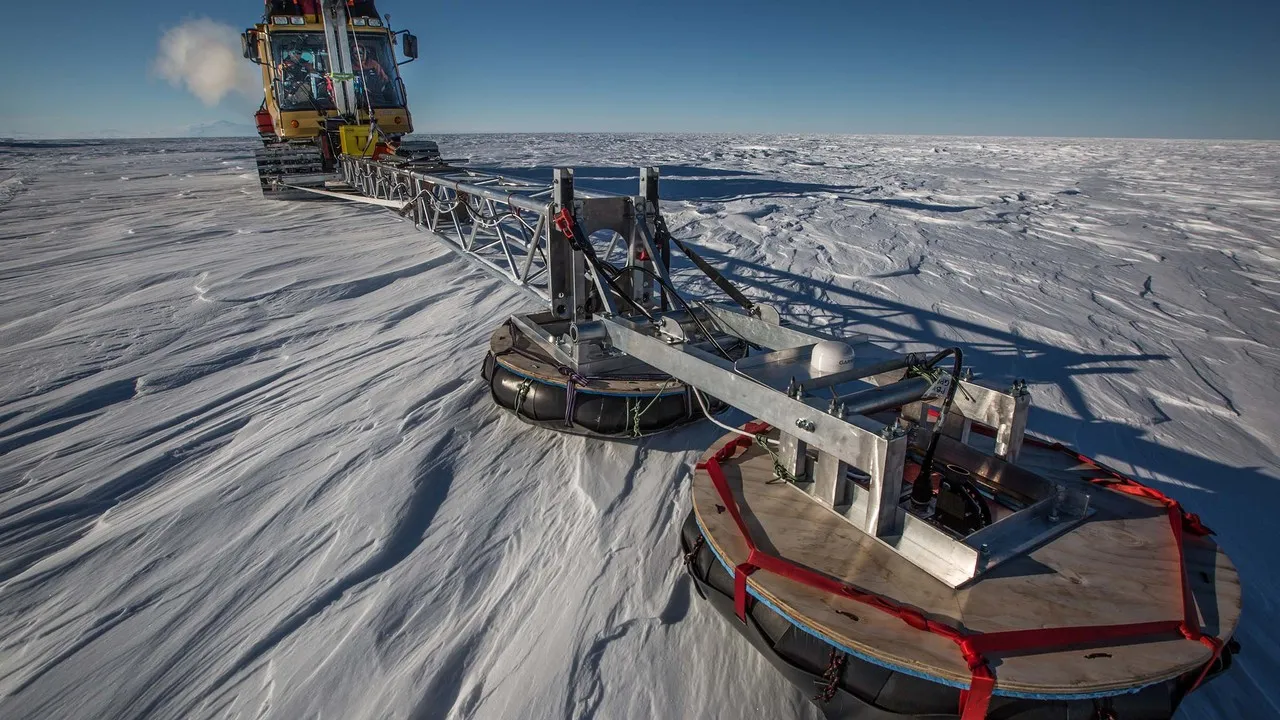

One very important project is trying to better understand the Antarctic sea ice thickness distribution. We've been able to monitor the extent of sea ice around Antarctica for 40 years with satellites, but its thickness is very hard to infer from space. We're now trying to measure that thickness from airborne platforms – a fixed-wing DC-3 aircraft – with an instrument called an EM Bird, which is an electromagnetic induction device. The EM Bird is suspended 80 metres under the aircraft to accurately measure the thickness of the ice below.

That’s critical information to understand how much sea ice is being formed in the Southern Ocean every year, because the sea ice acts as a big mirror, helping to reflect sunlight and mitigate its warming effects on sea temperatures.

You’re also studying the Ross Ice Shelf?

I’ve been involved in extensive surveys of the Ross Ice Shelf – trying to understand at what magnitude it’s melting. We’re trying to better understand the flow of glaciers coming off the continent of Antarctica and into the ocean. The Ross Ice Shelf is huge and holds back metres and metres of sea level rise – so it’s very important for New Zealand researchers to understand what is going to happen to it.

That kind of study involves a lot of fieldwork – can you paint a picture of what that’s like?

I've now done six laps of the Ross Ice Shelf. It’s mostly flat and white. But unfortunately, in certain regions, it's heavily crevassed. And you can't see those hazards visually, so, we use remote sensing technology to help us spot the crevasses and navigate a safe path across the Ice Shelf.

The traverse is over 1000 kilometres and takes us about two and a half weeks, driving 10 kilometres an hour. We are travelling with a huge amount of science and logistical equipment behind us in a convoy of three or four vehicles. I’m in the front vehicle with a colleague and our job is to make sure we don't drive into any crevasse fields.

There are massive sections where nothing is happening, and then suddenly that completely changes and we're mapping crevasses every 50 metres. So, you go from a very calm, boring environment for days and days to a high stress environment where decision-making is critical.

That must produce some stressful moments?

The worst scenario is when you have a whiteout or flat light, which a lot of people probably have experienced skiing, and there's no contrast, because the sun is clouded over – so the ground and sky merge into one. I've described it as like being inside a ping pong ball and it really has a strange effect on the brain.

You’re well prepared on these missions, but have you ever felt in immediate danger?

Not really, but there are times that really challenge you. Earlier this year we were heading back north from the traverse, quite late in the season. We're on our way home, just trying to chew through the miles, and the sun was getting lower and lower every day. The season was wrapping up, and everyone is trying to get out of there because the sun is going to disappear. And I just had this feeling of impending doom.

It crossed my mind that we were on the exact same route as Robert Scott and his men (who died on Ross Ice Shelf in (1912). And you just think of how they must have felt, starving to death and probably knowing they were not going to make it. I’ve never had a feeling like that before, where the daylight is running out and it feels like the walls a closing in.

Do you think New Zealanders understand how important the future of Antarctica is to us?

Antarctica holds back 60 meters of global sea level rise. So, a change to that continent will affect the entire planet. Having an understanding and appreciation of that is really important. That big refrigerator down there also modifies the climate of New Zealand, and I don’t think people really grasp that.

How do you effectively communicate the urgency of that issue?

It’s very difficult, because it’s such an abstract issue. The simplest way to put it is that we're changing the fundamental parameters of our environment. We built society statically in a climate system that is now changing, so all the infrastructure we built – where we built our homes, where we built our roads, where we decided to set up shop – is all now going to be threatened by the environment moving around it.

Does the scientific work your involved with give you some optimism?

I think technology will no doubt play a massive role in, firstly, how we respond to the changes we've already locked in, and secondly how we move to more sustainable use of energy in the future. So, technology has huge potential to help, but there is no way around the fact that we have to reduce emissions.

Don't miss a thing

Sign up to our newsletter to get valuable updates and news straight to your inbox.

)

)

)